They Could Be My Sons

By Hugh Taylor

January 2018

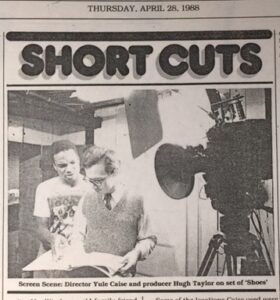

Yule Caise and Hugh Taylor on the set of the student film, SHOES at Harvard University in 1988

Seeing the old clipping, my first reaction is to wonder what on earth happened to all my hair. That, and how dorky do I look in a sweater vest and tie? The shot dates back to 1988, when I appeared with my friend, Yule Caise, in an article in the Boston Globe covering Yule’s student film, Shoes. I was the producer.

Shoes was a coming-of-age story set in the ghetto. It starred two teenage rappers, Kamal Jamau and Todd Holliday, portraying young men in search of themselves and the ultimate pair of unaffordable designer sneakers. It was a cautionary tale but also a projection of hope that things were going to get better for kids growing up in the inner city.

The film came out well, winning awards and launching Yule’s and my careers in the entertainment industry. The image of the two of us working on the film was part of the whole project’s appeal. Two college kids, one black, the other white, collaborating on a film about racial issues. It’s a hopeful image, one that we felt portended a more equal future with better race relations and fairness in the movie business and the country as a whole.

Though I hadn’t thought about the movie much in recent years, it remained a warm memory of success. Shoes reentered my life with a phone call from Yule a few weeks ago. Our conversation revealed the contrast between then and now.

Todd Holiday, on the set of “SHOES” in 1988

Thirty years provides perspective, offering lessons in what life is like versus what you expect it to be. Todd Holliday was tragically murdered in a drive-by shooting in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood in the 1990s. He left behind two small children. Johannes Schuster, who designed the film’s logo, was killed while on a photojournalism assignment in Iraq in 1991. He was following our film professors’ exhortations to “get close to the action” a little too well.

Todd’s family didn’t have a photo of him, so they reached out to Yule to see if he could locate one. Hence, the call to me. Looking through the old photos of the film shoot made me reflect on the unpleasant surprises of 2017. It made me think about the divergence from the vision of the film and the reality of present-day American.

Here we are, thirty years after embarking on this hopeful partnership between a black kid and a white kid on a film that sought to make a difference: Young men, born after the film was produced, marching with torches and screaming, “Blood and soil” while threatening to kill those who would dare object to a statue of Robert E. Lee. Young men, gleefully singing, “There will never be a n—r in SAE [fraternity.] Young cops, born in the 1980s, gunning down unarmed black men in the streets.

Many of these men are young enough to be my sons. Where did they learn to think and act like this? Did my generation teach them to hate? What happened over the last 30 years that made things come out so differently from what we envisioned in 1988?

Please don’t think I come at this question as some sort of smug post-racial paragon. I’m a 52-year-old white guy who lives in the suburbs. I will cop to having a variety of low-grade biases, fears and suspicions of non-whites. However, I was taught that no human being is superior to another. (Having had dozens of my relatives murdered by the Nazis was part of this story, too.) I was socialized to think about improving the status quo, not perpetuating it. That’s the message I try to impart to my sons.

In 1988, I thought young people were blazing a trail toward a new way of thinking about race in America. If we had been asked how we thought black and white people would be getting along in 2016, we would likely answered, “Better than they are today.” And yes, it’s true that in some ways, racial attitudes have improved. But still, if you had told me in 1988, “White babies born this year will march for white supremacism, arguing for the extermination and exile of black and brown people and Jews, surrounded by white nationalist militias armed with AR-15s, running people over with cars—and be given a pat on the back by the President of the United States,” I would have thought you were quite deluded. It turns out we were.

What happened? It’s a long, complex and multi-threaded story that probably no one could every quite fully understand. It’s the economy, the media, politics… It’s him, you know who I’m talking about. It’s everything and nothing. It’s human nature. It’s also America’s most basic story, one that never seems to end. The struggle on the streets today is simply the latest installation of an ugly conflict that’s been raging for over 300 years. We were naïve or arrogant (or both) to think we could make a difference.

Should we give up? I say no. I don’t have any brilliant ideas about what should be done, but we cannot stand by and just let this happen.