Privacy Perspectives

When did privacy become such a big deal? Most people probably didn’t pay much attention to the risk of having their privacy violated by a corporation or government agency until a couple of decades ago. Jerry Seinfeld once questioned Radio Shack’s right to know his address. “I give you cash for the batteries. That’s where this transaction ends,” he said. Oh, but no, it didn’t. Radio Shack was an early pioneer in the corporate invasion of privacy.

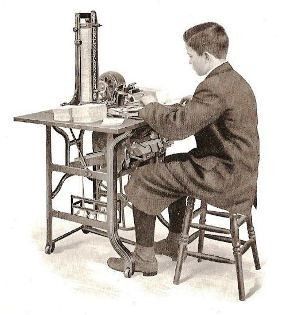

They weren’t the first, but earlier technologies for the invasion of privacy were rather quaint by today’s standards. Starting in the 1890s, a company could store your name and address on a metal slug (later, plastic) and print out a mailing label for you using what was known as the Addressograph system. Still, even with such incursions, it was possible, arguably until the advent of the Social Security system in the 1930s, for a person to spend his or her entire life in a state of complete privacy.

19th century invasion of privacy: the Addressograph machine

People were born at home. They died at home. Records of their lives might exist at the local church, on paper property records, the census or in the family Bible. There was no phone service, no utilities. No one had any idea who you were—and most people liked it that way.

Things have changed so much since Seinfeld questioned Radio Shack’s right to his data. We barely even know what privacy is any more. We may have a feeling for when our privacy is violated, like if someone “Doxxes” us, but for the most part, we willingly give up our privacy in return for free entertainment and other benefits, like the right to use apps.

However, privacy is part of laws like GDPR and California’s CCPA, give or take some significant legal issues discussed below. It’s also part of many legal agreements we make with entities that collect our data. For companies that hold our private, personal data, privacy issues carry risks in terms of litigation and compliance. As a result, cyber security people are now being tasked with ensuring compliance with privacy policies and laws.

It’s a complicated landscape. However, as is so often the case, when there’s a problem, solution providers appear on the scene to help you deal with it. Here are a number of perspectives on privacy from cybersecurity vendors who focus on the issue.

Discovering and Managing Private Data in the Enterprise

“It’s enough of a job to stay on top of the private data you deliberately keep in databases,” said Scott Giordano VP of Data Protection at Spirion. “What can cause real trouble, though, is the private data you don’t know you have.” Giordano, who is an attorney, explained how Spirion software discovers sensitive personal data that may be hiding in any number of places in an organization.

As Spirion has seen time and again, companies often have no idea how much private data they are holding inside of PDF documents (e.g. contracts) amidst a huge variety of unstructured data. The cloud compounds the problem, according to Giordano. “Companies may dump private data in the cloud by accident,” he said. “We help them find it, and then classify it so it can be protected.”

Spirion software has classification mechanisms that tag data according to a company’s privacy policies. This may seem basic, but it’s critical. “Some of the biggest breaches occur when a hacker finds data that should not have been sitting there, exposed to any old user on the network,” he shared. “It should not be that way.”

Automation is the key to a solution like Spirion. In any sizable organization, there is simply too much data to analyze and tag. The solution classifies data using terms or patterns of information in the document. Periodically, a document or data source will require a human assessment—calling “balls and strikes,” as Giordano put it.

Protecting Users’ Privacy

Philip Dunkelberger, CEO of Nok Nok Labs, approaches privacy from the perspective of protecting users’ private data. Nok Nok utilizes the Fast Identity Online (FIDO) standard to enable password-less access to data and applications. Password abuse or cracking of passwords is the root cause of 80% of data breaches, according to Dunkelberger. “Relying on passwords for privacy is a very naïve posture,” he said. “Most of us have dozens of online accounts. We reuse passwords. Our privacy is quite vulnerable as a result.”

To solve this problem, Dunkelberger took the initiative of creating FIDO. Since its launce in 2012, FIDO has become standard in virtually all browsers. FIDO protects user privacy by using public keys on both the device and the back end. The eliminates the need for a database of secrets, which is vulnerable to breach. It’s designed for ease of use, with simple PINs at the endpoint. “The fingerprint no longer travels over the wire,” Dunkelberger added. “This protects your privacy better than a password.”

Nok Nok is working to further commercialize FIDO. It has built a scalable server that is not covered by the FIDO spec. For example, if offers key recovery and NFC. The Nok Nok solution builds FIDO into SAML and OAuth security models. They company is now managing over 300,000,000 user keys.

Envisioning the Merger of Privacy and Security

Dana Simberkoff, also an attorney, serves as Chief Risk, Privacy and Information Security Officer at AvePoint, which offers data protection software, primarily on the Microsoft stack. From her perspective, the world is at a moment of intersection between privacy and security. “It’s time for a merger,” she shared. “Privacy has long been seen as a legal issue, a matter for the General Counsel, the fine print, so to speak. A checkbox for compliance managers. That is no longer a viable approach.”

“Privacy is truly an operational issue now,” Simberkoff added. “GDPR was the turning point, in our view.” As she put it, the law gives security responsibilities to a privacy officer. Typically, a privacy person did not report to security. Now, however, companies in Europe (and coming soon to the US) will have people on staff with dual privacy/security roles.

“You cannot have privacy without security,” she explained. “They go together and there will be no turning back.” One upside to this, is that privacy officers have now gained a measure of coolness.

“Security is cool and interesting. Privacy, not so much.”

Simberkoff also sees privacy through a generational lens. “Younger people today are in favor of greater openness,” she commented. “You can see this in how openly digital natives share their private lives online. But, as you mature, your sense of privacy changes. It’s like getting a tattoo. You might not think about how it will look in 10 years, but it will still be there in 10 years.”

What to do about this? Simberkoff thinks more, better education about privacy would help. The law also might need to step in and offer more robust frameworks for privacy. Right now, privacy is regulated by the FTC. State laws also covers privacy. “It’s a tricky issue,” she admitted. “We have a constitutional right of privacy, meaning the government cannot unreasonable search or seize my private property. However, privacy is not a cause of action, in legal terms. In the EU, privacy is now a fundamental right. The US might be headed in that direction soon as well.”

Resolving Contradictions in Privacy Law and Practices

Richard Bird, Chief Customer Information Officer (CCIO) at Ping Identity, sees a fundamental contradiction between the law and any reasonable definition of privacy. As he put it, “You can’t protect human data without protecting the identity of a human being.” From his perspective, the current regulations assume that personal data residing inside a corporation belongs to the consumer. However, American companies are not required to protect consumers’ identities.

“If I pretend to be you, I can get your data. That’s a huge problem,” he said. Data protection laws like the CCPA simply add more stringency to the concept of data protection. This does protect the consumer from abuse of his or her personal data to a certain extent, but it does not protect the consumer’s identity.

From Bird’s perspective, laws that mandate breach notifications are worse. “They’re informing you that your data has been stolen and, we’re really sorry, but we have no accountability for abuse of your identity.” Indeed, while the law punishes the hacker for identity theft (assuming that hacker can be found and prosecuted) the company that suffered the breach is not legally liable for the theft of identity.

A better policy, in Bird’s view, would be to require businesses that handle information associated with a human being to protect their data with a method of access controlled by the user. “It’s my data,” he said. “I should be in control of my identity, making it the key to granting me access to it. Identity is the core of security.”