Checking In On the GAO Report. Yeah, That One…

The news climate in the United States is such that important stories often receive less attention than they deserve. In case you missed it, in October of last year, the General Accounting Office (GAO) prepared a report on Weapons System Cybersecurity at the behest of the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Armed Services. The news was not good.

DOD Just Beginning to Grapple with Scale of Vulnerabilities

The report’s subtitle, “DOD Just Beginning to Grapple with Scale of Vulnerabilities,” is actually sort of funny, considering that the Department of Defense (DOD) has been warned about cyber vulnerabilities for 28 years now. It’s easy to be snarky about this, so I won’t, but seriously?

“Using relatively simple tools and techniques, testers were able to take control of these systems and largely operate undetected. In some cases, system operators were unable to effectively respond to the hacks.”

The stakes are high. In financial terms, the report notes, “DOD plans to spend about $1.66 trillion to develop its current portfolio of major weapon systems.” But, money is really the least of it. According to the report, “In operational testing, DOD routinely found mission-critical cyber vulnerabilities in systems that were under development, yet program officials GAO met with believed their systems were secure and discounted some test results as unrealistic. Using relatively simple tools and techniques, testers were able to take control of systems and largely operate undetected, due in part to basic issues such as poor password management and unencrypted communications.”

In one case, testers were able to guess the password to a weapon’s system in less than 10 seconds. “Even ‘air gapped’ systems that do not directly connect to the Internet for security reasons could potentially be accessed by other means, such as USB devices and compact discs,” the report stated, then added, “Weapon systems have a wide variety of interfaces, some of which are not obvious, that could be used as pathways for adversaries to access the systems.”

One might reasonably conclude that, in a war scenario, our entire military simply will not work. In other words, despite spending $750 billion a year on defense, the U.S. is defenseless.

It’s definitely worth a read, if for other reason than to catch tidbits like, “Using relatively simple tools and techniques, testers were able to take control of these systems and largely operate undetected. In some cases, system operators were unable to effectively respond to the hacks.”

Reading the report, it’s hard to come away with any conclusion other than that virtually every ship, plane, tank, missile, artillery piece, radar, communications system—and on and on—is completely vulnerable to cyberattack. In fact, it would straining credulity to suggest that the vast majority of the US military’s weapons have not already been compromised. And, interpolating the findings, one might reasonably conclude that, in a war scenario, our entire military simply will not work. In other words, despite spending $750 billion a year on defense, the U.S. is defenseless.

Media and Government Response to the Report

The report came out, followed by some murmurings in the press. The story was covered relatively well by outlets like Lawfare Blog and NPR. The New York Times’ David Sanger and William J. Broad covered the report in a story titled New U.S. Weapons Systems Are a Hackers’ Bonanza, Investigators Find. They observed that even the declassified details in the report “painted a terrifying picture of weaknesses in a range of emerging weapons, from new generations of missiles and aircraft to prototypes of new delivery systems for nuclear weapons.” The alarm was raised, but essentially ignored.

The Senate Armed Service Committee held a closed hearing on the matter in April, 2019, six months later. No one knows what was discussed at this hearing, but the guest list suggests it was a serious conversation. Witnesses included the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, the Director for Defense Intelligence and Major General Thomas E. Murphy, USAF, who is Director, Protecting Critical Technology Task Force at the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

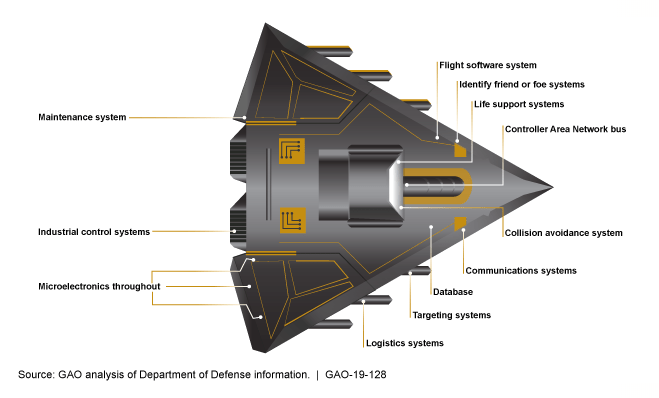

An image from the GAO report shows cyber attack surfaces on a hypothetical weapons system.

Industry Reaction

Industry response to the report has also been fairly muted. No one volunteered an opinion on the report at RSA in more than 50 vendor interviews I conducted there. When I asked about it, most people had heard about the report, but didn’t want to talk about it. One possible reason is that the findings are already so thoroughly understood in cybersecurity circles that there simply isn’t much more to say. Alternatively, some companies are already working with the military, so they don’t want to comment on the matter.

To be fair, it’s not as if these risks are not being addressed. The question is how best to mitigate them. The Senate Armed Services Committee held a hearing with defense industry people to discuss the report and related issues in March. One witness, Dr. William LaPlante, who serves as Vice President at Mitre National Security, offered a perspective on cybersecurity standards that’s worth repeating.

The DoD’s response to cyber vulnerabilities has been to mandate that defense contractors adhere to the NIST 800‐171 standard. This is a wise move, but a realist will see that it’s one with limited impact. As Dr. LaPlante explained the Committee, “There is no measure or target for outcomes associated with implementation of the 800‐171 standard. For instance, was less data lost? While standards may have the potential to improve performance above a baseline level, they quickly lag behind evolving operating environments and emerging technologies. Most importantly, they quickly become the target of our adversaries, who familiarize themselves with our standards and look for seams they can compromise.”

“There is no measure or target for outcomes associated with implementation of the 800‐171 standard. For instance, was less data lost?”

The standard can only do so much, even if it’s perfectly implemented. And, as we know from a constant drip of serious cyber attacks on defense contractors, compliance is not consistent. What else can be done? I put this question to several industry veterans, who offered their insights.

The findings of the report resonated with Michael Langer, Chief Product Officer of Radiflow, an OT cybersecurity company. Langer, who spent decades in senior cyber warfare roles in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), understands weapons systems’ cyber vulnerabilities. He’s faced comparable challenges in the past.

In Langer’s view, the problem is serious, but it can be addressed. “You have to attack the risk exposure from multiple directions,” he explained. “One end, you have the supply chain. A weapons system is almost always assembled from components sourced across what you could call the defense industrial base—a network of separate companies, each of which has to maintain tight cyber security controls. This is not easy, and the more companies you have, the more difficult it is.”

“There has to be a focus on testing these controls and remediating deficiencies.”

Langer’s recommendation is for the military to establish and enforce strong security policies at the sub-contractor level. “This is of course already going on, but as you can see from the report, the results are uneven. There has to be a focus on testing these controls and remediating deficiencies.” He admits, though, that the challenge is more addressable in Israel, where the defense industry is of more limited scope than in the US.

Then, there is the operational aspect of weapons system cyber security. “You have to assume that each weapons system, including its various sub-systems, is under constant attack,” Langer shared. “There are a number of different countermeasures for this problem, but you have to be monitoring all the time. For example, you can embed data-generating sensors throughout the system and watch for anomalies that suggest that the system has been penetrated.”

“There are a number of different countermeasures for this problem, but you have to be monitoring all the time. For example, you can embed data-generating sensors throughout the system and watch for anomalies that suggest that the system has been penetrated.”

“Monitoring will only get you so far, however,” Langer added. “Ultimately, it’s a command and control issue. The operational guidelines of the weapon, including the people who are responsible for its use, have to be part of cyber threat remediation. Depending on the military unit, this can be a comparatively strong or weak link the chain. The commander in the field needs to know when he or she is under attack, and then, what to do about it. Of course – all these should be part of cyber defense units and operational commanders training. The challenge is not that different from what we see in industrial facilities, but the consequences of a misstep are a lot more serious when it’s a ship, a plane, a missile… The GAO report is a warning to all militaries that they need to address these vulnerabilities.”

Darren Guccione, CEO & Co-founder at Keeper Security, which provides password management solutions, found the GAO report “alarming and concerning.” In his view, “There was a fundamental flaw in the creation of legacy weapons systems: Cybersecurity was not an essential, pervasive requirement of the weapons system during the planning and design process.”

“There was a fundamental flaw in the creation of legacy weapons systems: Cybersecurity was not an essential, pervasive requirement of the weapons system during the planning and design process.”

Guccione recognizes that government systems tend to have long refresh cycles. However, as he explained, “This creates massive cybersecurity vulnerabilities and budgetary constraints because dependent and interdependent weapons systems need to be upgraded, patched or modified – both on a stand-alone basis and at scale.”

Where many complex, legacy systems having dependent and interdependent subsystems exist, retrofitting and embedding cybersecurity protection becomes exponentially difficult. Guccione cited the example of an isolated network has a system that uses SSLv3. He observed, “When the system was isolated, the risk of exploitation of the vulnerability of SSLv3 was very low. But then, the network is ‘upgraded’ to interconnect with other networks and systems. Now, that system’s cyber risk has increased exponentially because of the new capabilities added to the system. This creates a plethora of potential vulnerabilities given that there is no cybersecurity plan in place to require a contemporaneous system patch or upgrade in order to mitigate cyber risk in those vulnerable systems.”

For this “can of worms,” as Guccione described the report, “The solution will require a proactive and adaptive mindset for bolstering initial systems through extensive retrofitting and rework. On a go-forward basis, a cybersecurity framework should be implemented covering all future planning, development and deployment of complex weapons systems.” It’s time, though, because, as he said, “We are, without any doubt whatsoever, in a cyberwar.”